Why China has been a growing study destination for African students

African students at Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University in Fuzhou.Credit: Xinhua/Shutterstock

Winnifred Kansiime was finishing her undergraduate degree in environmental health sciences at Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda, when she received an offer that she could not refuse: a place in a three-year master’s programme in environmental engineering at Xiangtan University in China, preceded by a year there learning Mandarin — with all expenses paid by the Chinese government. The course, which Kansiime completed in 2016, paved the way for her current pursuit of a doctorate in public health at Makerere. More than that, she says, “I wound up having the best time of my life in China.”

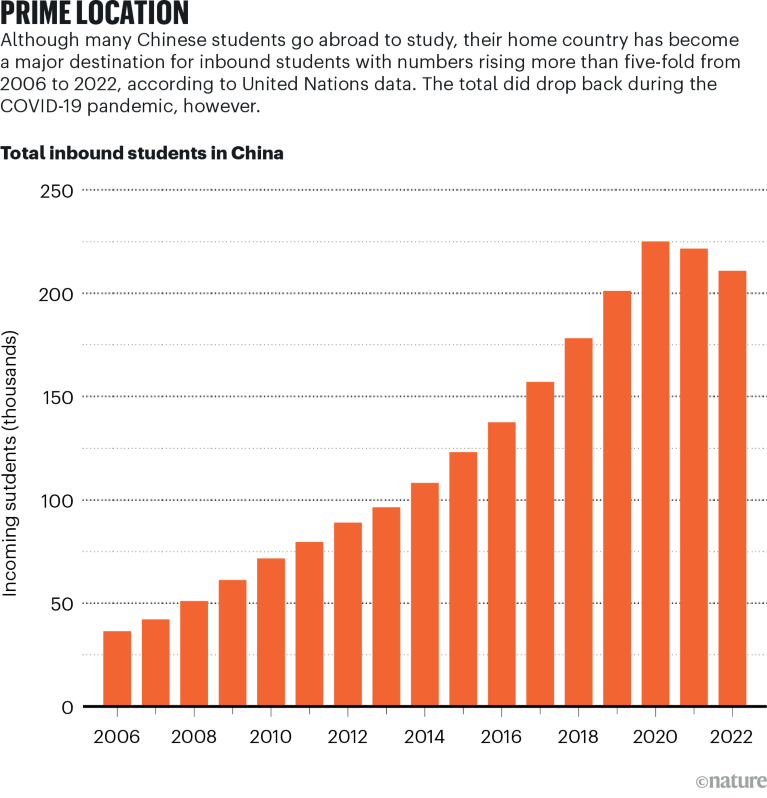

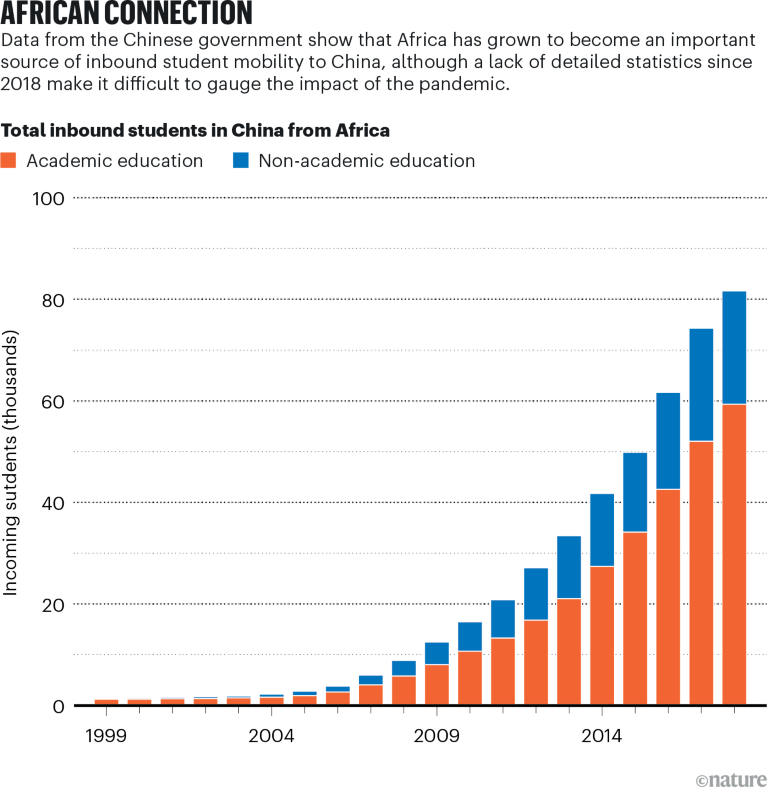

Kansiime is one among tens of thousands of African students who have pursued undergraduate or graduate studies in China, primarily in the subjects of engineering, science, business or management. Although African students have been studying in China since the 1960s, over the past decade their numbers have risen dramatically. In 2006, just 2% of China’s international students came from Africa; by 2018, that proportion had risen to nearly 17%.

Nature Index 2024 China

According to China’s Ministry of Education, of the 81,562 African students who were studying in China in 2018, 6,385 were pursuing a PhD — representing about 20% of all foreign students undertaking a doctoral degree in the country. In 2018, the Chinese government pledged to provide 50,000 scholarships for African students to pursue higher-education studies in China over the following three years. By 2020, China was outranked only by France as the top destination for African students pursuing higher education abroad, according to the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a think tank headquartered in Washington DC.

Detailed data on foreign students in China since the COVID-19 pandemic started in 2020 was unavailable at the time of writing. But in general, the country’s strict lockdown policies have had a negative impact on international enrolment, says Benjamin Mulvey, a sociologist at the University of Glasgow, UK, and author of Mapping International Student Mobility Between Africa and China. “Lots of students were locked out” of China, “and students were also locked in”, he says of the pandemic. Some foreign students, particularly those from Africa, also faced discrimination and scapegoating at the height of the outbreak. Some restaurants, malls and hospitals in China banned Black people from entering, for example, and some African students were thrown out of their apartments, Mulvey says.

In 2021, the Chinese government reaffirmed its logistical and monetary support for African students at the triennial Forum on China–Africa Cooperation, a multilateral meeting that is part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Launched in 2013 as a global infrastructure development strategy, the BRI is underpinned by economic and geopolitical motivations on China’s part and has so far reached around 150 countries. At the 2021 meeting, officials did not commit to a specific number of scholarships for African students as they have done in previous years, stating only that China will continue to train professionals through the programme. But assuming government support does come, Mulvey expects African student enrolment in China to pick up again soon.

Soft power

Chinese government scholarships have always been a big part of the draw for African students. Mulvey says they are “underpinned” by a desire to enhance diplomatic links between China and African countries. Some scholarships, therefore, “go to the children of politicians and business people in a less-than-transparent process”, he says. “But there are also students from quite disadvantaged backgrounds who receive scholarships.”

Although most African postgraduate students receive financial support, the majority of undergraduates still pay their own tuition. They often come from middle-class families and are attracted by the relative affordability of studying in China compared with North America or Europe. But whether they receive a scholarship or not, virtually all African students who study in China are beneficiaries of a deliberate Chinese government strategy to strengthen ties with the continent, says Wen Wen, a higher-education researcher at Tsinghua University in Beijing. “Nowadays, higher education is becoming part of geopolitics,” she says. “China has a very clear goal to project its influence in the Belt and Road countries, and African countries are definitely part of this initiative.”

Source: UNESCO

The Chinese government is “quite explicit that the purpose in giving these scholarships is improving soft power and having people strategically positioned in Africa who could open doors for Chinese business and industry”, says Natasha Robinson, a postdoctoral researcher in education at the University of Oxford, UK. Although this quid pro quo relationship is sometimes portrayed in a negative light, Wen sees it as mutually beneficial. “China helps to train African PhD students, doctors and engineers, and when those students return to their country, they bring back China’s academic atmosphere and scientific research standards,” she says. “From this perspective, I think it’s quite good.”

African students might also have “a sense that China is the future, and it’s good to have familiarity with it”, Robinson adds. “They already speak English, so having Chinese under their belt is really valuable.”

However, not every African student who studies in China has the positive experience that Kansiime did. If students are on the receiving end of racism or are disappointed in the calibre of the education they receive, then China’s goal of developing soft power can backfire, Robinson says. In such cases, African graduates “certainly come back knowing China, but they don’t necessarily come back loving China”.

Opportunities and obstacles

For most African students, the appeal of studying in China is multi-fold. First and foremost, China provides access to educational resources that usually are not available back home, Robinson says. “If you want to do any natural-sciences research, then China’s facilities are much superior.” But language barriers can pose a difficulty in making the most of these resources. “There’s only so much you can do in a year” of learning Mandarin, Robinson points out.

Winnifred Kansiime.Credit: Courtesy of Winnifred Kansiime

Kansiime, for example, was proficient enough after a year of intensive Mandarin tuition for general communication, but not for the technical language of her engineering courses, which were all taught in Chinese. She came to rely on online software and “super helpful” classmates and professors for translation assistance, she says. She also watched instructional YouTube videos and accessed free digital courses from universities in Europe and the United States to supplement the Chinese lectures. The silver lining of all this extra work, she says, was that she came away with a better grasp of the material.

On the other hand, Kansiime did feel like she missed out on developing a strong relationship with her master’s supervisor, who did not speak English fluently. This is a typical situation reported by African students, Robinson says. “There have been students we’ve spoken to who were told their postgraduate studies would be in English, but then turn up and find that their supervisor doesn’t speak English.”

Martha Muduwa, a doctor and clinical-trials coordinator at the Mbale Clinical Research Institute in Uganda, completed her undergraduate degree in medicine and surgery at Capital Medical University in Beijing in 2019. She had applied to universities in both China and the United Kingdom but opted for China in part because of the lower cost of tuition, which a family member paid. Muduwa’s courses were all in English, but she sometimes struggled to understand her professors, whose grasp of the language varied. She was confronted with other language-related disparities too, including an English library that was “just one tiny room”, she says, compared with the larger Chinese library that spanned three floors. She also learnt that the Chinese students and international students who were studying in Chinese were given “a lot more opportunities” than the students following programmes in English, she says, including a greater diversity of course options and a chance to participate in research.

Most international students missed out on many opportunities, but Muduwa made the most of things, she says, by learning to advocate for herself in the classroom and at a hospital internship. “If you were not pushy, you got nothing out of your internship,” she says. Many of her classmates “never even examined a single patient”, but Muduwa says she was able to get hands-on experience, including assisting in operations, by having a more forceful attitude.

Expanded worldviews

Studying in China can also provide African students with more intangible benefits. “It’s good to experience other cultures,” Kansiime says. “It makes you an open-minded person and willing to accept and understand other people’s views and perceptions of things.”

Muduwa adds that the Chinese friendships she made had “really enhanced my experience of their culture” and that she “absolutely loved the food”. African students — who typically live in international dormitories separate from Chinese students — also benefit from an opportunity to make friends from around the world. “You’re all foreigners in this place,” Kansiime says. “You have to mix and make your own community together.”

Outside of the campus environment, though, African students in China very often find themselves singled out for their race, Mulvey says. In public, Muduwa was constantly aware of people photographing or pointing at her, and some even touched her without asking for permission. “You’re on your phone on the subway, you’re minding your own business, and someone would start playing with your braid,” she says. Although most of this attention seemed to be driven by curiosity, she also saw overt racism, including job offerings that listed different salaries for Black or white English-language teachers.

Source: China Ministry of Education

Mulvey knows of some African students who remain in China to do a postdoc or take on an assistant professorship, but longer-term stays are “quite rare”, he says. Although there are more avenues now than in the past to get post-study work visas in China, it is still a very difficult process. In addition, “many African students have families and jobs back in their home countries”, Robinson says. “This, coupled with a feeling of foreignness in China, means that many choose to return.”

Researchers have yet to conduct large-scale studies of what happens after these former students return home, says Mulvey, including how, if at all, they use their degrees; whether they put their Chinese-language skills to use; whether they contribute in a tangible way to building positive relations with China; and the impression they take away from their time in the country. “There is very little research on this, though it is a crucially important avenue for future research,” Mulvey says.

In interviews Robinson conducted with 27 African students who formerly studied in China, a few did say that they were continuing to collaborate with Chinese colleagues. Robinson had expected the number of collaborations to be higher, she says, and typically in these relationships, “Chinese scholars would do the experiment and calculations, and African researchers would write it up”. For Africans returning home after years of study in China, this “is not an amazing outcome”, she adds. Although Africans who studied in China often have the skills to do experimental research, the problem is that they might lack the resources and facilities at their home institutions, and therefore are reliant on Chinese colleagues.

Kansiime, for her part, says she would “highly recommend” studying in China. Muduwa is more measured. “I would recommend China to African students, but with caution,” she says. “They’d have to manage their expectations and consider the fact that they might not get 100% of what they want from the university experience.”