Meta AI system is a boost to endangered languages — as long as humans aren’t forgotten

Machine translation works well for widely spoken languages — but languages with a smaller digital footprint struggle.Credit: Zhang Hengwei/China News Service/Getty

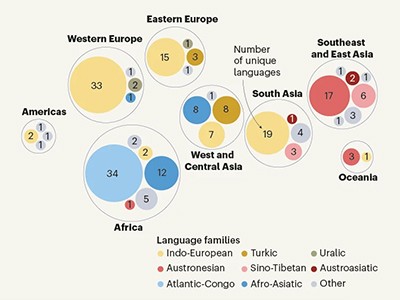

In this week’s Nature, a team that includes researchers at the technology company Meta describes a method of scaling up machine translation of ‘low-resourced’ languages for which there are few readily available digital sources1. The company’s automated translation systems will now include more than 200 languages, many of them not currently served by machine-translation software. These include the southern African language Tswana; Dari, a type of Persian spoken in Afghanistan; and the Polynesian language Samoan.

It’s an important step that helps to close the digital gap between such neglected languages and languages that are more prevalent online, such as English, French and Russian. It could allow speakers of lower-resourced languages to access knowledge online in their first language, and possibly stave off the extinction of these languages by shepherding them into the digital era.

Meta’s AI translation model embraces overlooked languages

But machine-learning models are only as good as the data that they are fed — which are mainly created by humans. As machine-translation tools develop, the companies behind them must continue to engage with the communities they aim to serve, or risk squandering the technology’s promise.

Of the almost 7,000 languages spoken worldwide, about half are considered to be in danger of going extinct. A 2022 study2 predicts that the rate of language loss could triple within 40 years. The dominance of just a few languages on the Internet is one driving force: it’s estimated that more than half of all websites are in English, and the top ten languages account for more than 80% of Internet content.

The researchers, based at Meta AI, Meta’s research division in New York City, the University of California, Berkeley, and Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, set out to expand the number of low-resource languages that their model translates as part of Meta AI’s ‘No Language Left Behind’ programme. They selected languages that were present in Wikipedia articles, but had fewer than 1 million sentences of example translations available online.

Read the paper: Scaling neural machine translation to 200 languages

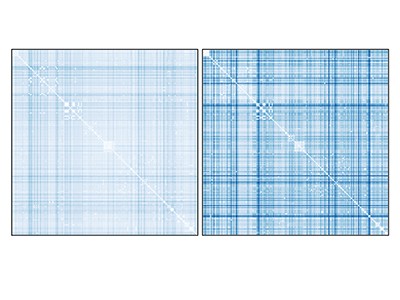

This work doubles the number of languages made available by a previous iteration3, and makes improvements to translation quality. The researchers employed professional translators and reviewers to create a ‘seed’ data set in 39 of the languages, and developed a technique that allowed them to mine web data to create parallel data sets in the remaining languages. They also generated a list of some 200 ‘toxic’ words for each language, to identify translations that could, for example, constitute hate speech.

The involvement of human specialists is time-consuming and expensive — but crucial. Without them, algorithms would be trained on poor-quality data generated by artificial intelligence (AI), creating more errors. Models would then harvest this content and create even more poor-quality text. William Lamb, a linguist and ethnographer at the University of Edinburgh, UK, who was not involved in Meta AI’s programme, says that this is already happening for Scottish Gaelic, for which most online content is generated by AI. Scottish Gaelic is one of the low-resourced languages in the Meta programme for which the content was professionally translated. Human expertise is also important for languages that lack certain vocabulary. For example, many African languages do not have bespoke terms for scientific concepts. The research project Decolonise Science employed professional translators to translate 180 scientific papers into 6 African languages. It was initiated by Masakhane, a grassroots organization of researchers interested in natural language processing.

Such specialists are in short supply, however. This is one reason why researchers and technology companies must include communities that speak these languages, not just in the process of creating their machine-translation systems, but also as those systems are used, to reflect how real people use those languages. Researchers who Nature spoke to say that they are concerned that not doing so will hasten the demise of the languages and, by extension, their associated cultures. Without continued engagement, working on machine translation could become another form of ‘parachute science’, in which researchers in high-income countries exploit communities in low-income countries.

“The words, the sentences, the communication, are void of the values and beliefs encoded in the languages,” says Sara Child, a specialist in language revitalization at North Island College on Vancouver Island in Canada and a member of the Kwakwaka’wakw people. As AI propels more languages into the digital space, “I worry that we lose even more of ourselves”. This human element must not be ignored in the rush towards a universal translation system.